Battle of the Nocturnals

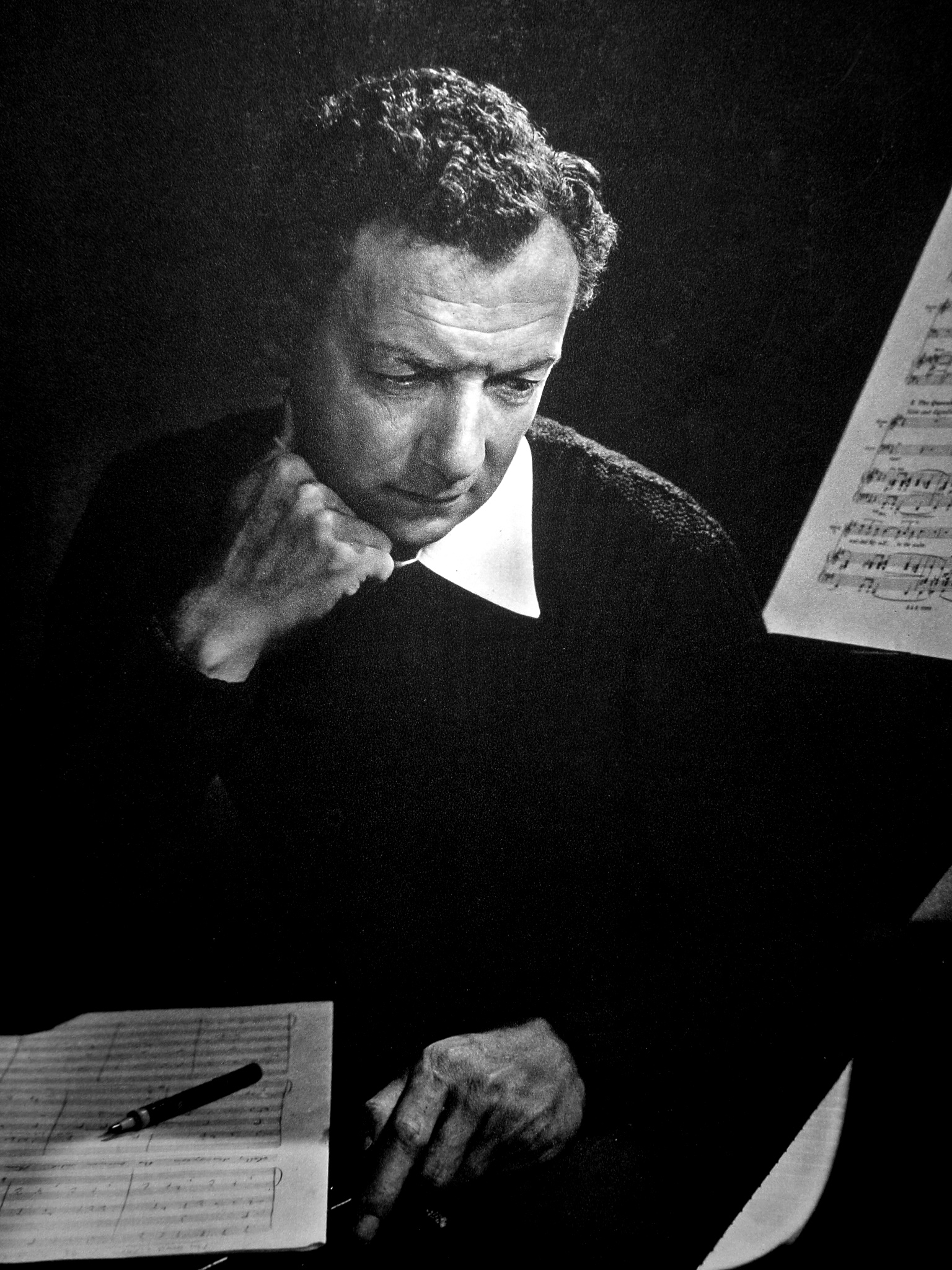

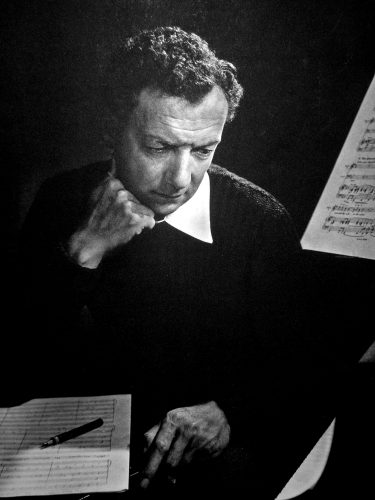

Benjamin Britten’s Nocturnal after John Dowland is one of those rare pieces that almost single-handedly changed the history of an instrument: dedicatee Julian Bream’s premiere at the 1964 Aldeburgh festival made waves in the contemporary musical establishment, leading to top-flight composers writing several other substantial pieces in the following years. Almost fifty years after its conception, the piece remains popular, featuring on countless recordings and in historical and analytical writings (check out, for example, Stephen Goss’s illuminating article in the EGTA Guitar Forum #1).

I thought it would be interesting to juxtapose a few recordings of the Nocturnal to see the range of interpretive approaches that a piece of this caliber encourages. I am not comparing or evaluating these recordings against each other, or against an idealized model—I’m simply hoping to show their differences as a testament to the piece’s musical depth. Sifting through my iTunes library I came across three examples that offer a wide range of contrast — I could have easily chosen others, but I purposely avoided Julian Bream’s own terrific interpretations if only to ensure I would not suffer from a sort of “originality bias” in the process. The three recordings in this roundup are by Craig Ogden (from Tippett: The Blue Guitar), Edin Karamazov (from Come Heavy Sleep), and Antoniy Kakamakov (from Inquieto).

Surface differences abound, most obviously in terms of the instruments chosen by each player. Karamazov’s stands out, as the disc, which pairs the Nocturnal with Bach’s BWV 1004, is recorded entirely on archlute (!!!). The instrument brings a sort of wispy, ethereal quality to the music that is perfectly fitting; moreover Karamazov does not shy away from employing the archlute’s extended lower range to thunderous effect. Purists might be turned off, but let’s not forget that Britten’s original concept for the piece involved the lute, and it wasn’t until Bream insisted for a guitar piece that the composer changed his mind.

Ogden’s Smallman, conversely, brings a modern and distinctive sound to the music—rich, clear, if a bit hollow at times. Kakamakov is the only of the bunch to align himself with recordings of yesteryear, employing a 1967 Hauser II borrowed from the Harris Guitar Collection for the occasion. His tone is perhaps the perfect mix of clarity and mysticism, at least to my ears: in his hands, the Hauser II growls assertively in the fast passages of Very Agitated and in the furious ending of the Passacaglia, but it can also whisper beautifully in the quieter and slower sections of the piece.

Tempo and rhythm also differ between each player’s approach. Ogden’s recording is the fastest at under eighteen minutes; the Australian-born guitarist also offers the most accurate reading of the score, as exemplified in his Passacaglia, which maintains the same tempo throughout (despite the tendency for many players to accelerate as things get busier and louder, there is no such indication in Britten’s score!). Both Karamazov and Kakamakov, on the other hand, approach the phrasing in a less strict way; Karamazov may be a bit over the top for the more conservative listeners—his gutsy approach to the movement’s finale varies wildly in tempo before settling into the slowest and quietest Come Heavy Sleep of the bunch. Once again, Kakamakov seems to split the difference between the other two performers, flexing the rhythms without losing touch with the score, and offering a clearer balance of modernism and romanticism in his reading.

What is perhaps most surprising is that each of these very different performances manages to be perfectly successful as a listening experience—a product of the artistic maturity and interpretive coherence of the three artists in question, but also a testament of the piece’s ultimate power. With its microscopic thematic and motivic development, its large-scale formal design, and the emotional punch packed in the harmonic trajectory of the music, Britten’s Nocturnal still makes for a challenging and rewarding benchmark for the modern guitarist. Here’s to hoping for a thousand more recordings of the caliber of Ogden’s, Karamazov’s, and Kakamakov’s.

Paul Hardy

Thanks for this; interesting.

I was surprised when I bought Julian Bream’s 2nd (EMI) recording — how much more purpose & expectancy there seemed to be in the passacaglia than the other versions I have heard. Quite spellbinding